Since this open source project really started to gather momentum in December 2015 after a posting on Hacker News, I’ve been asked several times to talk about the genesis of HospitalRun and why a few people working for an under-resourced health care charity would be foolish enough to start yet another open source EMR/HIS project.

This article tries to answer that question: Why HospitalRun?

Note: Click here for the Google Doc justification paper titled, “Why HospitalRun?”

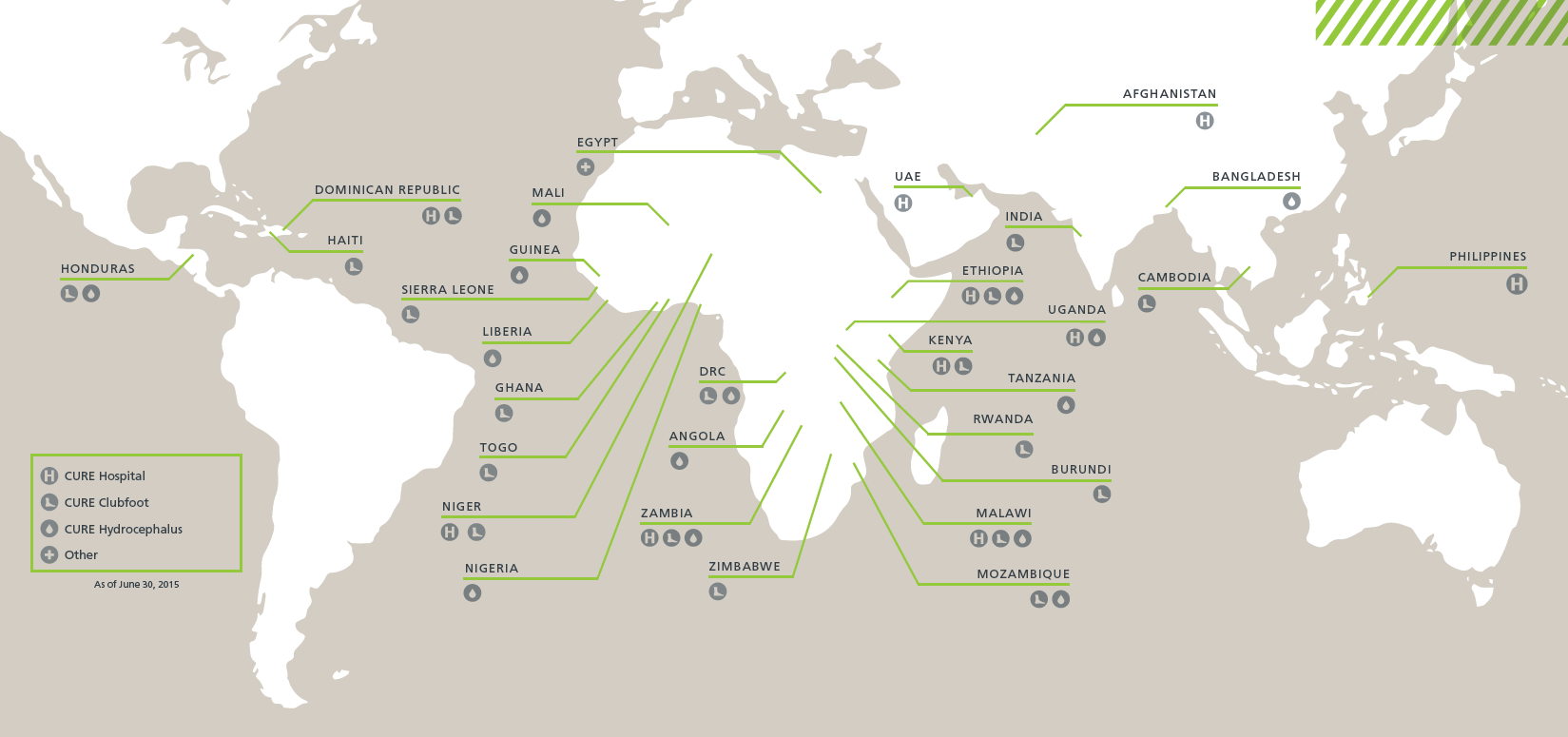

The journey that led to HospitalRun started in 2012 at a CURE International hospital in Kijabe, Kenya.

Like all CURE hospitals, CURE Kenya primarily treats children with surgically correctible conditions. Things like clubfoot, bowed legs, cleft lip and palate, and other conditions that are commonly addressed by public health initiatives in areas of the world with more resources - all these are the primary mission of CURE. Issues of essential surgery and the kids CURE treats tend to be on the bottom of priority lists in the resource-scarce environments of low-to-medium income countries (commonly referred to as “the developing world”).

Back in April 2012, I was in Kenya to check out the effectiveness of a real-time patient reporting platform CURE had just released, to see how our embedded bloggers were performing their day-to-day job.

That’s when I saw this.

The medical record system at the CURE hospital in Kenya, 2012

Not surprisingly, this was the medical records system for a hospital that had been providing life-changing treatment to children throughout Kenya since 1998. In and of itself, paper-based records in low resource environments are not that surprising, and there are plenty of commercial and open source projects that have tried (one might argue unsuccessfully) to truly solve the issue of moving health management away from paper record-keeping to electronic systems.

However, it was when I saw this that I knew we had an even bigger problem to solve.

Doctors and clinicians at CURE's hospital in Kenya, loading medical record bins onto an ambulance that is headed out on a mobile clinic

You see, that day, I was heading off campus with a team from the CURE hospital to conduct what we refer to as a “mobile clinic.”

Because CURE provides such specialized care, we attract and treat patients from throughout the country, 3-4 times per year and in regions throughout Kenya, a team from the hospital will visit an area 6-8 hours away from the hospital to see hundreds of children and their parents in one day. Some of these children are patients receiving long-term follow-up care. The majority are parents desperate to find a cure for their little boy or girl, bringing them to a CURE clinic to learn whether or not we can help.

I watched as our dedicated staff organized a clinic of 400 children and their parents, digging through boxes of medical records, often loosing valuable time and energy, trying to assign new patients to new charts, asking patients to shuffle their medical records through the queues, and sometimes loosing track of who had what data. The team did (as always) an admirable job, and at the end of the clinic, dozens of children had been scheduled for life-changing surgeries… but it was clear there was a problem.

Experiencing that mobile clinic helped me feel that problem. This wasn’t just an EMR (electronic medical record) problem. This was an offline problem.

As a software professional, I knew that the right, long-term decision for any software solution was to go to the cloud, but this environment presented two big challenges - challenges that (heretofore) have dissuaded technology professionals from moving to a cloud solution for low resource parts of the world:

When I got to my office in Pennsylvania, I shared what I saw, and (subsequently) my colleague John started working with a design paradigm called Offline First.

The core concept of Offline First is simple: stop treating the lack of connectivity in a web-based app as an error condition. Instead, make the application resilient to interruptions in connectivity. Native frameworks and modern browsers as well as many modern web frameworks provide tools to make this not only possible but increasingly transparent to not only the end user but also the application developer.

So, we started working with the technology. That did not mean we wanted to start an open source project. Far from it.

Back in 2012, we never had the interest or inclination to try to tackle an entire hospital information system, led alone start an open source project. Instead, we decided to explore offline first principles in service to a challenging-but-smaller problem, a research database need we had for a program inside CURE called CURE Hydrocephalus.

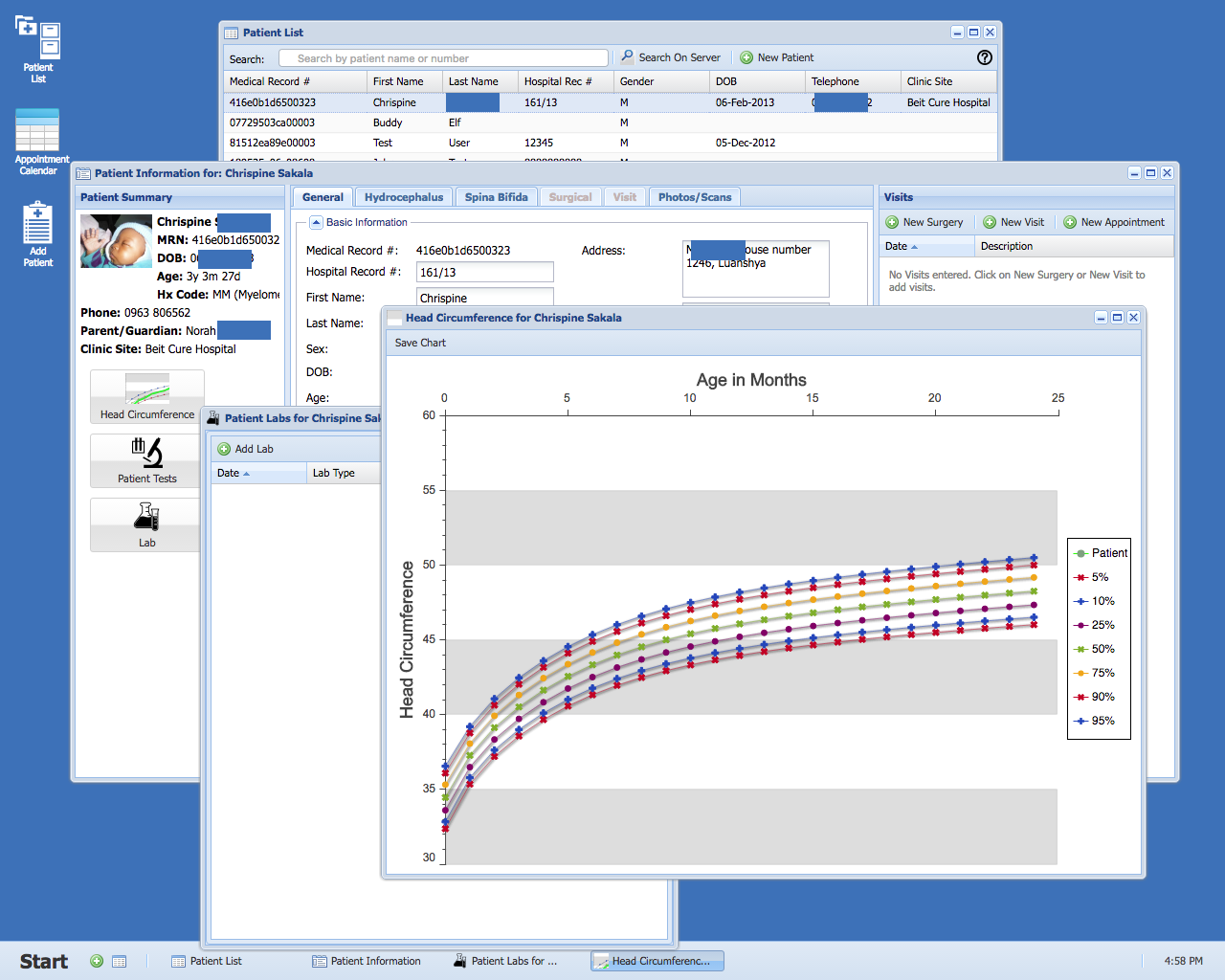

Reviewing patient records in the CURE offline first hydrocephalus database - an offline first web application built for Chrome

By Fall 2012, that research database was deployed in 14 countries, primarily in subSaharan Africa. We learned a lot from that project, but now we needed to address the larger issue of a complete HIS (hospital information system) solution.

Like all good programmers, we’re lazy - disinterested in re-solving problems. We already had too much work to do supporting CURE, and if there were appropriate, affordable solutions out there for our HIS requirements, we would have loved, loved, loved to have found one.

We just happen to work at the intersection of two sectors that needs a lot of innovation: non-profit and health care.

So, we spent 2013 evaluating technologies and trying to find a solution that could meet the needs of the CURE International network.

We knew that:

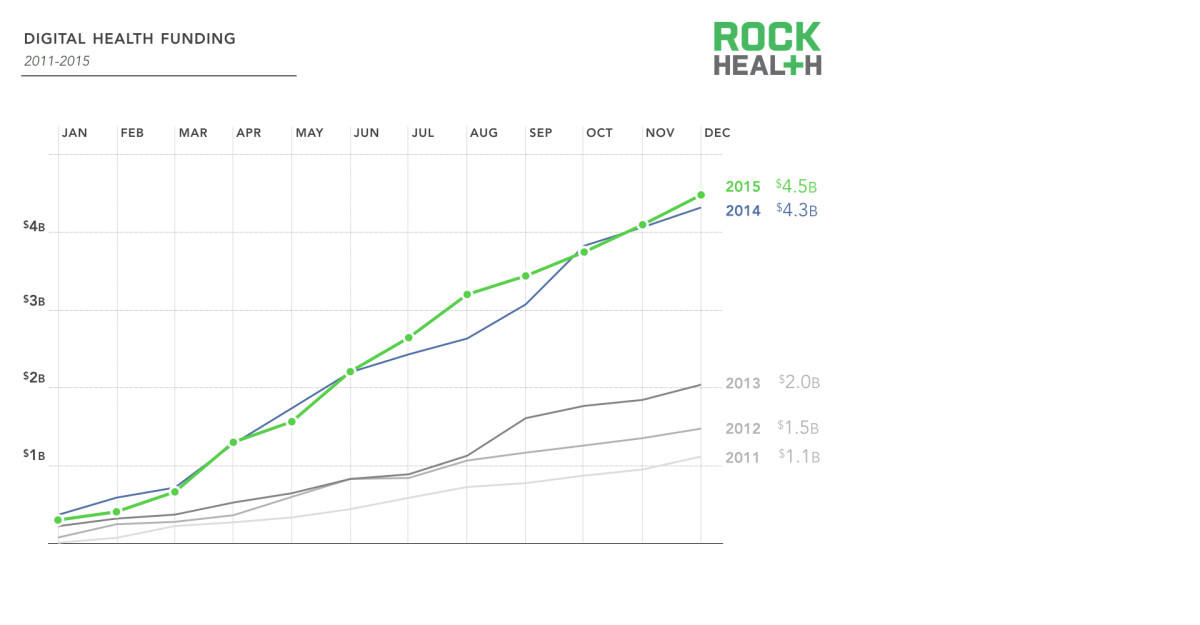

And, we knew that the tide was turning with regards to digital health.

Rock Health's 2015 analysis demonstrates a significant trend in the rise of digital health solutions (and therefore investment)

So, in early 2014, we re-examined the work we had done with our offline first hydrocephalus research database and determined to take what we learned there and apply it to a brand new effort.

But if we were going to start over, we were convinced we needed to go open source. The only sustainable project would be one that was useful for thousands of potential facilities - not just the CURE International network.

So, we set out to seriously examine the existing open source health projects. Many of them had done some good work, but for a variety of reasons - either because of a lack of ability to influence the community, the very clear lack of focus on UX, or the practical need we would have to completely rearchitect their undelying technology - we were faced with the option we didn’t want: starting a new project.

The HospitalRun project was unsuspiciously launched in 2014 at a piece of D-level commercial real estate in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania.

We had a sense that if CURE International - a network of hospitals that was receiving some source of funding from the US, Canada, and the UK - was struggling with this issue, that there could be thousands of other facilities in low-to-medium income countries with the same problems. However, validating that sense with facts was harder than you might think. There seemed to be no clear research answering the question: how many hospitals are in low-to-medium income countries?

So, we did some research ourselves.

We put together a mashup of UN and WHO data in order to try to estimate how many hospitals are in low-to-medium income countries. The result of that work is published here, and we referenced our estimate, nearly 14,000 hospitals in low-to-medium income countries, in our first justification paper, titled “Why HospitalRun?” Side note: A year later, I was speaking with another CTO and contributor to HospitalRun about that research and was told that our numbers were way off - that we completely underestimated.

The bottom line is that there’s a huge, unaddressed need.

So in early 2014, we launched the HospitalRun open source project, choosing Ember and PouchDB for the front end project and Node and CouchDB for the back end.

In September of that year, we did the first early (probably too early) deployment of the system at the CURE hospital in the Philippines, and we’re scheduled to release a 1.0 by or before April 1, 2017.

But we were not interested in running the favour-of-the-year open source health project, merely choosing today’s “cool tools” and fading out in 3-4 years. Instead, we’ve worked to establish very specific goals for why we’re doing what we’re doing. Those are:

This is about more than supporting internationalization (which HospitalRun does). Building software for the developing world is about embracing the realities of lower-resource settings as a driver - rather than a constraint - for innovation. When you can’t health-care-consultant your way out of a problem, it reframes the opportunity to produce a truly useful solution that is focused on meeting the needs (technical, business, and otherwise) of those environments.

Low-to-medium income countries need a solution focused on their needs rather than porting the constraints of Western medicine to the majority world

The lack of attention to user experience or even the user interface in electronic health solutions has generated a track record of confusion and cost, as high-paid consultants are needed to enforce less-than-optimal solutions onto teams. The settings for which we’re building have no such conquistador-like luxury, where teams of health care IT professionals can enforce change. In many of these settings, there may even be little financial incentive to enforce record-keeping policy.

Yet rather than lament those constraints, we’re choosing to see these settings as an opportunity to focus on the needs of the user(s) - clinical and administrative. So we set out to build a solution that people might even (…dream with me) enjoy using, and we brought UX expertise into the core maintainer team of the project to help hold us accountable to producing the kind of solution that strives to delight users.

Hiring a team of highly-paid/highly-qualified consultants because you've "burned the ships" on your decision to implement an EMR/HIS isn't a realistic option in low-to-medium income health care environments

But we didn’t want to limit our usability goals to just clinical or even administrative users. What if we could build a system that was easy to setup, administer, and upgrade? And what if we could build an open source project that was… wait for it… easy to contribute to? (No more spending a day polishing your secret decoder ring to make a contribution.) Could we build a system that allows someone to make a meaningful contribution in one 8-hour day?

That’s what we set out to do with usability: make HospitalRun the most ambitious AND delightful open source health project in the world - for users, administrators, and contributors. We still think we have a long way to go, but that’s the goal - making usability #1.

A recent survey of Western health care practitioners found that 20% of their time was being spent on administrative tasks that (arguably) had little to do with improving the quantity or quality of care being provided. Much of that time was caused by - rather than improved by - the software they were using.

"How are we saving time for users of HospitalRun?" is one of the primary considerations in any feature.

With HospitalRun, we saw the opportunity to give health care professionals in exceptionally constrained environments back the only resource we can’t make more of: their time.

Going forward, we’re purposing to metric the system to not only inform requirements but also to baseline the time it takes to accomplish common tasks so that future feature development can seek to improve on those measurements. The result of every feature should be time given back to more doctors, nurses, and administrators so that their attention can go where it should - on the patients and families they serve.

Not only because offline first met our “carry records into the field” requirement but also because we believe that it’s just the right thing to do with modern business applications, we wanted to make offline first a core principle of the project from the beginning.

HospitalRun embraces the principles of offline first

Deploying software isn’t like installing a refrigerator that you spec out, buy, plug in, walk away from, and expect to work perfectly until the compressor dies. This is clear to the business world, as the rise of software as a service models are driving home not only the effectiveness but the lower total cost of ownership in signing on to a service that has ongoing, continuous improvement and maintenance.

Yet far too often (and even particularly today with open source projects), we treat software solutions like a utility that is installed once and expected to meet all our needs until the day it is replaced (much like a kitchen appliance). The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Innovation and support need the opportunity for continuous upgrades, and HospitalRun is committed to a future where the HospitalRun code is only a part of the overall open source project.

We’re building an open source service.

Software isn't a refrigerator, so HospitalRun is building a service

It seems to us that HospitalRun:

holds a tremendous opportunity to partner the NGO, government, and tech sectors in a problem that has mutual interest and benefit.

It’s almost as if, by working together… we just might have a fighting chance of changing the world.

Moreover, through initiatives like our Hack Day events, we’re seeing tremendous opportunity to engage those with programming, design, devops, project management, and marketing backgrounds to use their true gifts in service to a cause that has utility, opportunity, and innovative technology.

Thanks to our friends at New Relic for contributing this video

One of the things we’re putting a lot of energy into for HospitalRun is the usability experience for contributors. Contributors are the fuel that make any open source project like this possible, and we need contributors in coding, design, user experience, marketing, project management, product requirements, and devops.

If you think you’d be interested in getting involved in the project, we’d love to have you start by joining our Slack. At minimum, share this post with someone or someones to help us meet more people who might be interested in contributing.

To date, dozens of people have contributed to what’s been accomplished already with HospitalRun, and hundreds more are actively tracking with the project. On behalf of the entire HospitalRun core team as well as the kids and families we’re serving together - to everyone who’s taken part in the project in these early days, for those who will contribute in the weeks, months, and years to come, and most-importantly for the people who make HospitalRun a regular and recurring part of their contribution to the world, thank you!

There are literally thousands of children, mothers, fathers, grandparents, and the like who’s lives can, have, and will be impacted… perhaps even saved… by all of us working diligently and collaboratively on this project.